A couple of weeks ago, a video that made the rounds on social media showed an Egyptian man chanting during an Oromo conference in Egypt that the Oromo will get their rights and come to power in Ethiopia.The video resulted in minor disturbances in the otherwise stable Egyptian-Ethiopian relations for a few days, with a spokesman from the Ethiopian government accusing “elements” in Egypt of financing, arming and training armed groups in Ethiopia to undermine the government.

Egyptian authorities swiftly denied all such accusations, reiterating its full support and respect of Ethiopia’s sovereignty.

Although the rift was short-lived and has since been forgotten, it is a fact that the presence of the Oromo people in Egypt has been increasing as of late.The Oromo are the single largest ethno-national group in northeast Africa. In Ethiopia, they are estimated to comprise 50 million out of the country’s total population of 100 million.

Although the Oromo group is the largest among the country’s 80 ethno-national groups, it is the most oppressed group in Ethiopia and is subjected to torture and arrests from the government for demanding their rights.

Among the Oromo community, the majority is Christian, while Muslims represent an almost equal percentage of the community. Muslims, Christians and individuals of other religions living together in harmony without any discrimination within Oromia territory.

Since the Ethiopian government decided to implement the so-called “Integrated Addis Ababa Master Plan” to expand the Ethiopian capital, which is classified as one of the capital cities witnessing the greatest growth, it started dislocating the Oromo people from their farms without giving proper compensations.

Oromo demonstrations surfaced in Ginchi – about 80 kilometers southwest of the capital – in November 2015, with the Oromo protesting against the selling of the nearby Chilimongo forest, land seizures and the ongoing evictions of Oromo farmers.

Human Rights Watch accused Ethiopian security forces of killing 400 people during the protests. The chaos from the protests resulted in the imposition of martial law in the country, which remains under effect until this moment.

Last August, the Oromo and Amhara groups – which, together, form 80% of Ethiopia’s population – protested against the government for marginalizing the two groups, depriving them of their rights and barring them from holding top positions in the country.

Clashes during the protest resulted in the death of seven protestors who were calling for the release of political prisoners, freedom of expression and an end to human rights violations.

The Ethiopian authorities’ violations against the Oromo people have pushed many of the latter to flee the country, with some of them seeking refuge in Egypt.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Egypt, there were 11,192 Ethiopian asylum seekers in Egypt as of September. The number increased noticeably after the clashes between the Oromo and the Ethiopian authorities.

“Of course there’s a significant increase in numbers of Ethiopian refugees,” Tarek Argaz, a media official at UNHCR, told Egyptian Streets. “Since a year and a half, the number of asylum seekers was around 5,000.”

“The reason behind the increased flow of Ethiopian refugees to Egypt is that the Ethiopian authorities can’t arrest us here,” said 25-year-old Abdi Boushra, Director of the Oromo Volunteering Association School in the upscale Cairo neighborhood of Maadi.

Boushra says he fled Ethiopia after being detained for a year after being accused of being a member of the Oromo Liberation Front, an armed group that is outlawed by the Ethiopian government.

“You’ll be oppressed just for being an Oromo; I was a teacher and I was telling students how to protest peacefully against what our territory is facing and the violations the government made,” Boushra told Egyptian Streets.

“I got arrested for a year. Then I fled from Ethiopia to Sudan. I’m like many people who fled from Sudan to Egypt by smugglers through the desert. We paid around USD 300 to reach Egypt.”

Boushra says he spent three months in Sudan but described his time there as a “nightmare,” saying that Sudanese authorities extradite asylum seekers back to Ethiopia.

“If we went there, we will be killed,” Boushra says. “We never imagined to live in Egypt before because of the different culture and language but we come here to feel safe.”

Ashraf Melad, a lawyer and researcher on refugee affairs, described the legal situation of Ethiopian refugees in Egypt.

“The 2014 Egyptian constitution insisted to protect any asylum seeker but there’s no refugee law in Egypt. Egypt is only permitting asylum seekers to live on its land,” Melad told Egyptian Streets. “In case of committing crimes, the Minister of Foreign Affairs alerts the country of the asylum seeker who committed the crime.

“In [Sudan’s case], there’s an implicit convention between the Sudanese and Ethiopian governments of extraditing Ethiopian opposition and asylum seekers. It’s a deal which had no place in Egyptian-Ethiopian relations,” Melad added.

“The UNHCR is keen on giving each refugee his right and make sure that he deserves our help. We decreased the period for discussing the papers of people who seek asylum after they got the yellow card to live legally in Egypt from 28 months to 16 months to accept him as a refugee or not,” UNHCR’s Argaz said. “I consider this as an achievement because we have an increasing flow and a limited budget.”

Noura Mohamed, a house maid who fled from the conflict in Oromia with her 14-year-old son, resorted to smugglers to help her make her way to Egypt through Sudan, like many other Ethiopians fleeing their country.

“The [situation] in Oromia was unbearable. The security comes to arrest you in your home just for being Oromo,” Mohamed told Egyptian Streets. “The government killed my father during clashes.”

Mohamed says that, after working as a maid in Kuwait, she returned to Ethiopia, where she and her husband were detained for demonstrating “and for being an Oromo citizen in the first place.”

Mohamed was released after three months, while her husband is currently still in prison in Ethiopia.

“I wanted to bring up my only son, so I decided to flee no matter what will happen; there’s nothing worse than what we experienced,” Mohamed says.

However, she says that she is struggling in Egypt, where her monthly salary is EGP 1,500 but her rent is EGP 1,000 per month.

“The UNHCR gives me EGP 1,050 in annual expenses for my son but of course this isn’t enough,” she says.

To add to Mohamed’s woes, schools are not accessible to many asylum seekers in Egypt, making it difficult for her to secure an education for her son.

“Asylum seekers have no right to [enroll] their children in Egyptian schools; there are schools for refugees but we noticed that many Oromo children evade these schools because they’re irrelevant to their identity and language,” Boushra says.

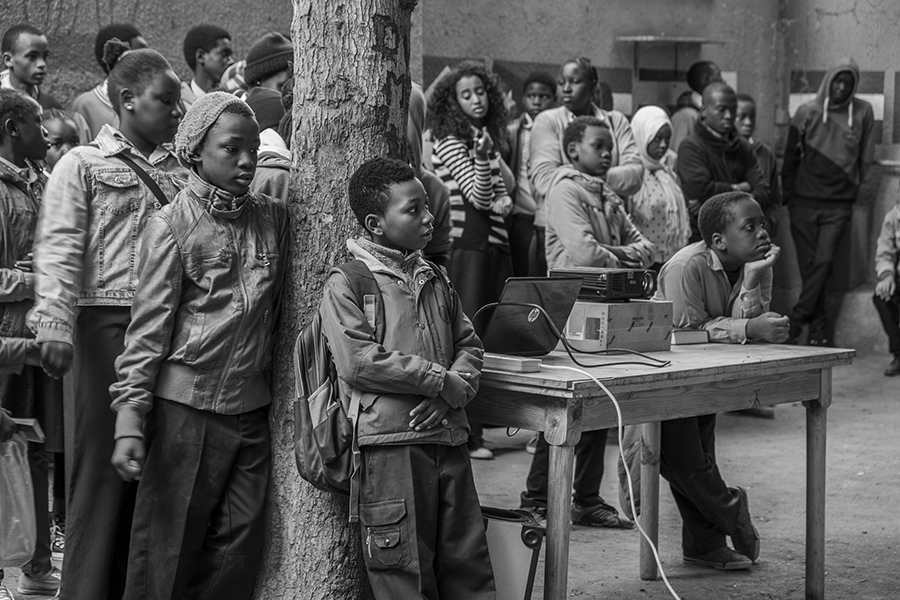

In an attempt to address this issue, Boushra says that the community decided to establish a school to teach Oromo children the Oromo language, as well as English, Arabic and other subjects such as math and science.

“We are working in the school as volunteers and there are no fees for children,” Boushra says, adding that the school currently has 150 students but remains free of the supervision of any educational authority.

The school was established in hopes of helping the Oromo people in Egypt maintain their identity as they work to integrate themselves into the society as a whole.

While a number of Ethiopian refugees say they don’t face racism or ethnic discrimination in Egypt, seeking refuge in Egypt is not without its challenges.

Everyday, many refugees who enter Egypt illegally gather in front of the UNHCR headquarters in the 6th of October satellite city, waiting for their turn to be accepted as asylum seekers and begin integrating themselves in Egyptian society.