ESPN.com

Archive

He was 6 when his father was killed, his body returned to the family's home on a makeshift stretcher.

He was 17 when his grandfather was killed, caught in the crossfire of a war that has been raging for 20 years.

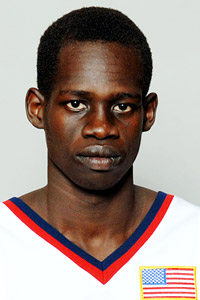

Dau Jok is not merely a victim of violence. He is a byproduct of it, born into its grasp and reared in a world where AK-47s were more readily available than pen and paper.

Until Jok, who just finished his freshman season at Penn, came to the United States eight years ago, the word peace was as foreign to him as the snow that greeted him when he settled in Des Moines, Iowa. In the Southern Sudan, the place Jok calls home, war is not news. It's life, a two-decade long battle between the Africans and Arabs that has claimed an estimated 2 million lives and left a country in such poverty and disarray that people there are referred to as the "lost generation."

But while outsiders and even international health organizations struggle to maintain hope, one 18-year-old believes steadfastly in it.

Jok, the child of violence, has plans to bring that rare gift of peace to his home country.

Peace will come in the form of soccer balls and basketballs, an after-school program and in time, a school building. Mostly it will come in the form of human kindness.

It sounds simple but Jok knows it will work.

How? Because it worked for him.

'Project For Peace'

Dau Jok believes he can bring a message of hope and peace to his native Sudan. His aims to deliver that message through his organization, the Dut Jok Youth Foundation, providing, among other things, education and opportunity. He'll provide updates of his travels for ESPN.com. Dau Jok: My mission in Africa

"There are a lot of people who took a chance on me, who told me I could be somebody," said Jok, who played as a reserve for the Quakers this season. "It's amazing when I look at myself, at who I was and who I am now. It tells me it can be done. You just need to show these kids that somebody cares for them, that not only can they be somebody, they already are somebody."

Jok's dreams are far more than a lofty vision. They are slowly becoming a reality. He has established the Dut Jok Youth Foundation, named in honor of his late father, and last month was named one of the recipients of the Kathryn Wasserman Davis 100 Projects for Peace award.

On Wednesday he and teammate Zack Rosen joined 12 other Penn students for a 12-day trip to Rwanda as part of a service project. When his classmates return home, Jok will continue on to the Southern Sudan, arriving in his home for the first time since 2003. Jok will blog about his trip for ESPN.com.

"I'm more excited than I am worried," Jok said. "It's like a dream come true. There's so much I want to get done."

The day they brought home the lifeless body of his father, a general in the Sudan People's Liberation Army, Jok's immediate reaction was to grab a gun himself.

The 6-year-old boy wanted revenge.

When kids in Des Moines teased him about his shoddy English or his gangly basketball skills, Jok's first instinct was to respond with his fists.

Fight or flight? For Jok, it wasn't a choice.

"We spent many hours talking about the idea that violence is not the answer," said Bruce Koepple, who served as a mentor for Jok in Des Moines. "That wasn't his mentality at first."

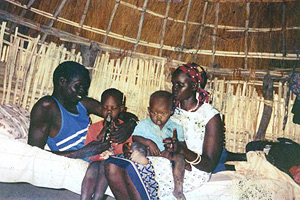

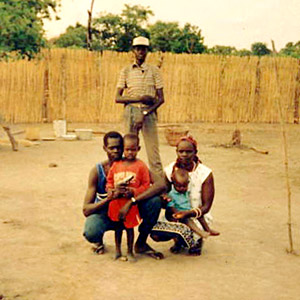

Jok came to Iowa -- as culturally and meteorologically opposite a world from Sudan as you could envision -- with his mother and three siblings, the end of a circuitous journey for the family after Dut Jok was killed. Initially they moved to Rumbek, a larger town in Sudan and then continued on to Uganda.

In December 2003, they came to the United States, settling in Des Moines because of a large Sudanese refugee population there.

Like most kids in Africa, Jok grew up playing soccer, albeit a makeshift version -- "we would blow up balloons and wrap them in bandages" -- but in Iowa he discovered basketball. Jok spent hours in the local Y, mimicking the moves of the other kids he played against.

He continued to hone his game, attending skills camps and perfecting his jumper. His size -- he's 6-foot-4 -- and 3-point shooting ability were enough to attract interest from some colleges but Jok was looking for more than just basketball.

He wanted an education. The kid who grew up writing in the sand because his school had no books or paper maintained a 3.9 grade-point average at Roosevelt High School.

When the University of Pennsylvania called -- with the hook of basketball and the promise of an Ivy League education -- Jok didn't hesitate.

"Sports gave me discipline," he said, "and academics, that's the way to a better life. It's the combination for me. If I didn't have that balance I wouldn't be where I am. I wouldn't be in a position to help people."

Dau Jok is apologizing.

In the middle of answering a question about what he hopes to do with his $10,000 in grant money and with his foundation, Jok stops and says, "I'm sorry. I know I'm talking a lot, but I'm really excited."

The excitement is contagious. He is a burst of energy and a font of ideas, a kid who has his head in the clouds yet remains grounded to reality.

"He has been on a mission since the first day I met him," Koepple said.

If we don't develop the leaders of tomorrow, we will never develop our country. They need to understand that there is more to this world than what they know. There are opportunities if you open your mind.

--Penn freshman Dau Jok

That mission finally has a direction. Jok has long believed that the secret to ending the strife in the Sudan lies in the hands of its children. Through education, encouragement and, most of all, options that don't include violence, Jok is convinced that this generation can help restore the lost generation.

He conjured up the notion of a foundation named in honor of his father six months ago, imagining an organization that could provide the infrastructure needed to bolster kids. He would take the lessons he learned in the United States and apply them to Sudan. There would be real soccer balls and basketballs for kids to play with and to keep them busy. Girls, often married away before they are 16 and currently allowed to play only volleyball, would be introduced to new sports, their self-esteem bolstered.

There would be an after-school program where kids could work on their academics as well as learn about anger management and the spread of HIV. His foundation would sponsor a mandatory weekly service day, forcing kids to work productively and help one another; down the road, the country could host a national holiday, bringing together kids from every ethnic group in a collaborative effort to break down barriers.

And someday, if Jok has his way, there will be a secondary school, built with money from his foundation.

"It's a lot, I know, but I want to harness the potential of our youth," said Jok, who was inspired by his late uncle, Manute Bol. "If we don't develop the leaders of tomorrow, we will never develop our country. They need to understand that there is more to this world than what they know. There are opportunities if you open your mind."

What was once a plan now actually has some heft thanks to the Projects for Peace grant.

The four-year-old program began at the insistence of Davis, who just before her 100th birthday put up $1 million, challenging undergraduates to develop programs that could contribute to peace. She has since reissued her pledge annually, offering $1 million more each time.

When Jok decided to begin his foundation, he turned to Penn professor Dr. Harriet Joseph for help. Joseph is the director of the university's Center for Research & Fellowships, and a self-described "basketball junkie."

Impressed by his idea and stunned to learn about his background, Joseph went to Cheryl Shipman, who specifically handles students' applications for grants and fellowships.

By then, the Project for Peace deadline was a little more than a week away.

"I remember it was an Ivy League [road game] weekend," Joseph said. "Dau was writing the application on the bus and sending it to Cheryl. We had no idea if it would work but we decided to let it fly and see if it goes. And it went."

Jok's proposal for the Dut Jok Youth Foundation was one of 104 awarded the $10,000 grant.

Armed now with his grant money and a donation of more than 1,000 soccer balls that will await him when he arrives in Sudan, Jok hopes to meet with the country's ministers of sport and education and talk about his plans.

The visit -- which will extend until June 12 -- will be an emotional one for Jok. He returns to the place where his father and grandfather were killed, a country he hasn't laid eyes on since he was a small boy. There was a time, Jok admits, that such a trip would surely stir his anger and give rise to the cauldron of violence he long ago buried inside him.

Not anymore. Jok, who has family he is eager to visit, returns home not as an angry child but as a man with a mission.

"I'm a voice for the kid who understands nothing but violence," he said. "I'm a voice of a kid who can't go to school. I'm a voice of a kid who doesn't have food to eat or water to drink. The work doesn't stop here. There is lots to be done."

As Jok speaks, it is hard not to believe that he, barely a man himself, is the person to do it.

"He's going to change the world," Koepple said, without a trace of sarcasm. "I have no doubt about that. He will change the world."

Dana O'Neil covers college basketball for ESPN.com and can be reached at espnoneil@live.com. Follow Dana on Twitter: @dgoneil1.

No comments:

Post a Comment