Secret deals between army putschists and the jihadists threaten the military campaign as Bamako politicians demand retribution

The strange pact under which President Dioncounda Traoré appointed the serial putschist Captain Amadou Sanogo as head of the military reform committee in a grand ceremony in Bamako on 13 February exposes the contradictions at the heart of the government. It also raises questions about the fractured command of the national army and its willingness to fight alongsideFrench and West African forces in northern Mali. These doubts will probably speed up the timetable for the United Nations’ involvement, as requested by France and now discreetly backed by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

The idea is that the 7,000 West African forces would be subsumed into a UN peacekeeping operation, paid for by the UN Secretariat in New York. UN Political Affairs officials would work with ECOWAS to organise and supervise national elections. That, at least, is the French and West African plan but UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon remains far from convinced.

Just five days earlier, soldiers loyal to Capt. Sanogo were in a firefight with a unit of paratroopers at the Djikoroni base in Bamako. President Traoré’s appointment of Sanogo to head the Comité militaire de suivi des réformes des forces armées et de sécurité, which was strongly supported by ECOWAS, is to lure Sanogo away from his military base at Kati, south of Bamako, into an office in town where he will no longer control troops. In fact, Sanogo’s equivocation over the launch of France’s intervention on 11 January had already made him lose face among his military supporters.

The main reason for that, we hear, is that he had been plotting a coup against the Traoré government in early January. The plan was for a twofold strike: Sanogo’s troops would knock out the Bamako government as jihadists from Iyad ag Ghaly’s Ansar Eddine forces began their southwards march on 10 January. Several officers in Sanogo’s inner circle, such as ColonelYoussouff Traoré, have links to Ansar Eddine, according to security sources in Paris.

Sanogo’s plan was to present himself as the realist who had reached a deal with the jihadists and saved the south: that would have left his junta dominant in Bamako and the south in return for recognising Ag Ghaly as the new leader of the north.

The Sanogo-Ag Ghaly axis

The overthrow of Traoré would have blocked the West African intervention approved by the UN Security Council in December. Sanogo and his allies seem to have calculated that this would call the bluff of the ECOWAS forces, even if he would appear to preside over the partition of Mali. At the same time, Ag Ghaly had concluded that the peace talks with the Traoré government hosted by Burkina Faso were going nowhere. Algeria had pressured Ansar Eddine and Ag Ghaly, who is well known in Algiers, to talk to Bamako. Yet by early January, it was clear that Algiers had lost its influence over Ag Ghaly and could not stop him from launching a fresh offensive.

The overthrow of Traoré would have blocked the West African intervention approved by the UN Security Council in December. Sanogo and his allies seem to have calculated that this would call the bluff of the ECOWAS forces, even if he would appear to preside over the partition of Mali. At the same time, Ag Ghaly had concluded that the peace talks with the Traoré government hosted by Burkina Faso were going nowhere. Algeria had pressured Ansar Eddine and Ag Ghaly, who is well known in Algiers, to talk to Bamako. Yet by early January, it was clear that Algiers had lost its influence over Ag Ghaly and could not stop him from launching a fresh offensive.

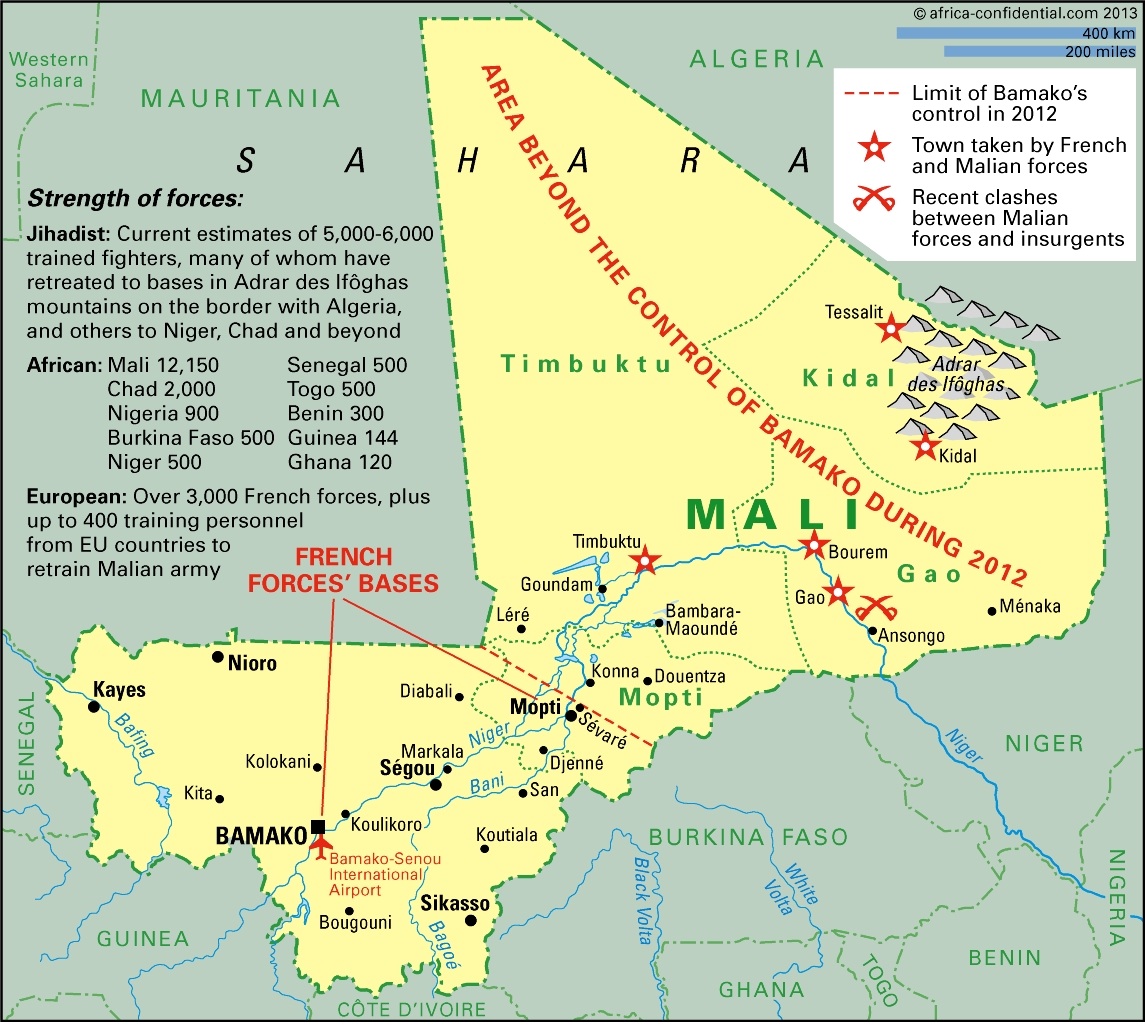

The jihadist push southwards aimed to forestall the Mission internationale de soutien au Mali(Misma) by seizing the military airbase at Sévaré and other key positions around Segou. Ag Ghaly’s attack was to provide the pretext for another putsch in Bamako and the new regime under Sanogo would negotiate. The fighters from Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb and theMouvement our l’unicité et le jihad en Afrique de l’ouest may have found Ag Ghaly’s plan less than compelling. They retreated very quickly from Konna and Diabali after 11 January, leaving Ag Ghaly’s mainly Malian fighters to take the full brunt of the French counterattack.

Algeria's meddling

Ministers in Bamako openly criticise Algeria for its ‘unhelpful meddling’. In 2010, Algeria established the Comité d’état-major opérationnel conjoint, which was meant to be a forum to coordinate with Mali, Mauritania and Niger against regional jihadist fighters but was also seen as a way to fend off French operations. CEMOC achieved little other than a few side deals between Algeria’s sécurité militaire and its regional counterparts. To the fury of Mali’s Defence Minister, Colonel Yamoussa Camara, Algeria did nothing to stop supplies from its southern provinces to the occupying jihadists in northern Mali. The subsequent attack on the In Amenas gas plant on 18 January, aided by collaborators inside the plant, exposed the failures of Algeria’s own powerful security services.

Ministers in Bamako openly criticise Algeria for its ‘unhelpful meddling’. In 2010, Algeria established the Comité d’état-major opérationnel conjoint, which was meant to be a forum to coordinate with Mali, Mauritania and Niger against regional jihadist fighters but was also seen as a way to fend off French operations. CEMOC achieved little other than a few side deals between Algeria’s sécurité militaire and its regional counterparts. To the fury of Mali’s Defence Minister, Colonel Yamoussa Camara, Algeria did nothing to stop supplies from its southern provinces to the occupying jihadists in northern Mali. The subsequent attack on the In Amenas gas plant on 18 January, aided by collaborators inside the plant, exposed the failures of Algeria’s own powerful security services.

Algiers had kept open communications to both Sanogo and Ag Ghaly. Some in Sanogo’s personal guard had been trained by Algeria. There is no evidence that Algeria was complicit in the Sanogo- Ag Ghaly deal although it may have suited President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s government, which saw France’s intervention as exacerbating instability in the region. Algeria’s opposition crumbled once the jihadist offensive began and it quietly granted France overflight rights.

After the last month’s military push by France and the African forces, there is a renewed focus on the political route ahead for Mali. The government and the transitional Assemblée Nationale have now approved the creation of a negotiating commission to tackle the grievances of the north. The Presidency Secretary General, Ousmane Sy, is looking at who should be involved in the negotiations. It is not yet clear how the commission will work and whether northern interests will be represented or be part of a wider forum.

France is encouraging the Bamako government to include a wide range of northern politicians, activists and business people in the talks. However, it is trying to be discreet and is not making specific suggestions about members. The ground rules are that no northern groups linked to terrorism should be included. That rules out the Mouvement national pour la libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) and the Mouvement islamique de l’Azawad (MIA), which peeled off from Ansar Eddine last month (AC Vol 54 No 3). The main facilitator for the process is likely to be Burundi’sformer President Pierre Buyoya, who is the African Union’s Special Representative in Bamako. Traoré faces pressure from hardline nationalists in Bamako, who oppose any concessions to the Tuareg, whom they blame for facilitating the jihadist takeover. This may explain the government’s issue of arrest warrants for MNLA leaders this week. France said nothing about the warrants which could make its position more difficult, especially in Kidal (see Box). Many politicians in Bamako believe that France’s former President Nicolas Sarkozy was financing the MNLA as a means to pressure the failing government of President Amadou Toumani Touré.

Foreign funds could start flowing soon now the European Union has unblocked 250 million euros (US$333.85 mn.) in aid. France has relaunched its bilateral development support and the International Monetary Fund is preparing a transitional economic plan. The priority is quick-impact programmes to restore water, power and other basic services in the north. That would encourage people there to see practical benefit from the expulsion of the jihadists.

The timetable for negotiations is complicated by the plan to hold elections for a government which would have the legitimacy and credibility to embark on major structural reform to the political system and economy. Many Malian politicians talk about a ‘transition to the transition’. There is widespread agreement that Traoré and his ministers must give way to an elected government. It may be possible for some dialogue over northern issues to start before elections, although it is unlikely that any long-term changes could be agreed under Traoré.

No special deal for the north

Elections will change the dynamics. Candidates in the south are likely to take a tougher stance on the north to court electors. That will make truly national negotiations more difficult, whether on political devolution or development spending. Many Bamako politicians insist there would be no special deal for the north; nor is the idea of making Mali a federation or even confederation gaining much ground.

Elections will change the dynamics. Candidates in the south are likely to take a tougher stance on the north to court electors. That will make truly national negotiations more difficult, whether on political devolution or development spending. Many Bamako politicians insist there would be no special deal for the north; nor is the idea of making Mali a federation or even confederation gaining much ground.

Uncertainty also hangs over the political timetable. Traoré has promised elections by 31 July but that would mean voting in the rainy season, when some communities are hard to reach and many Sahelian villagers are preparing the fields and planting seeds. Now it seems the most likely time for polls would be between October and December, after the harvest has been gathered in.

Copyright © Africa Confidential 2013

http://www.africa-confidential.com

http://www.africa-confidential.com

No comments:

Post a Comment